In August 2008, I boarded a plane in Newark and spent the 4-hour trip to Salt Lake City writing my dad’s eulogy. I was 31 and remember thinking, “Is this young to lose a parent? I’m an adult, but I feel young.” I don’t suppose there is ever a right age for this or any loss.

In honor of Father’s Day Weekend, I dug out what I wrote 17 years ago — and I was surprised by how many moments mentioned here made their way into my book “Raising Awe-Seekers.” Small but core memories from a dad who delighted in knowing all-the-things!

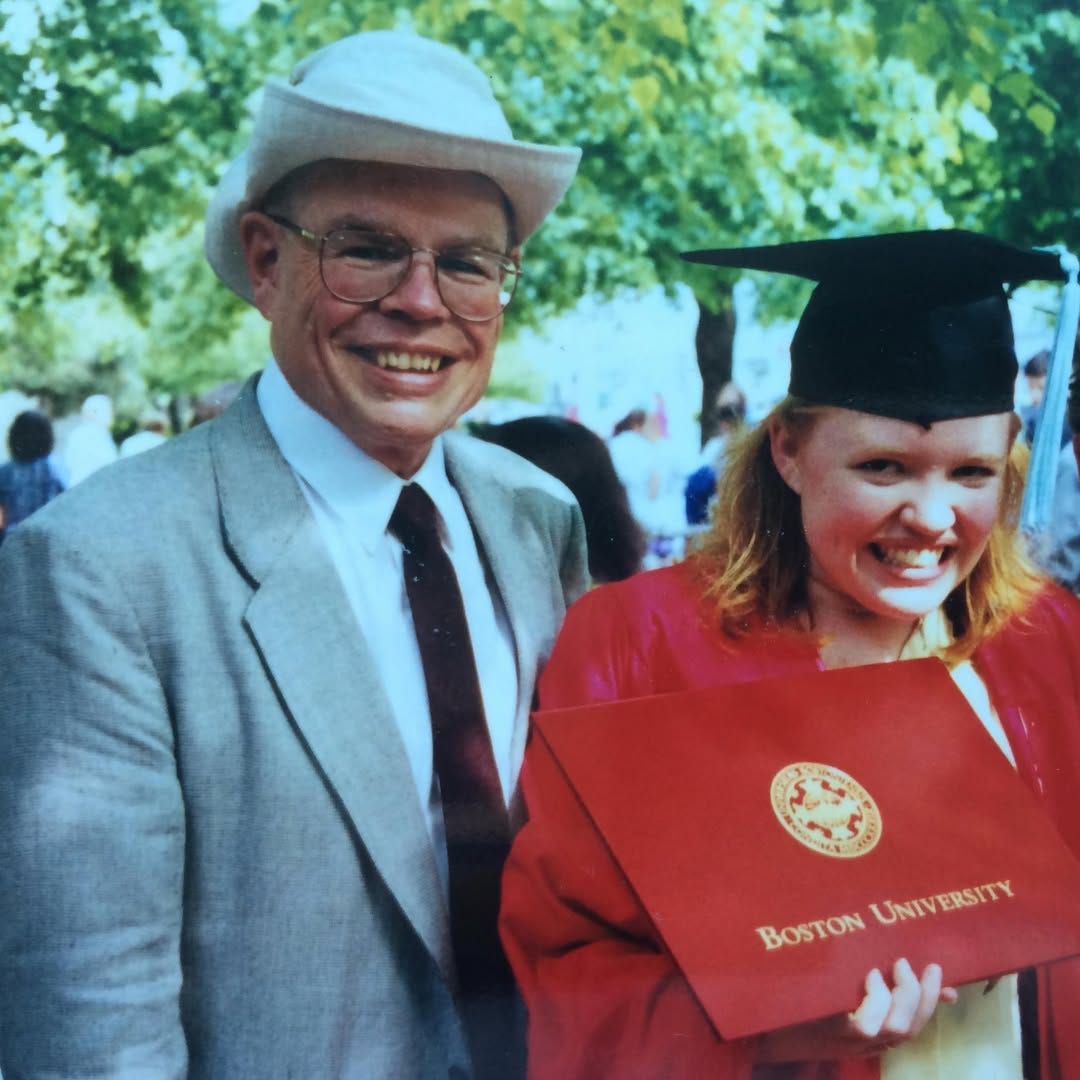

Here’s a short excerpt from my talk that day + a bonus photo of my dad and me taken at my college graduation.

A Eulogy for My Dad

I’m not sure when we — the five kids — realized that our father wasn’t exactly typical. Didn’t all dads occupy their restless children during church by scribbling probability problems and the Fibonacci sequence on the back of the program? Not every family got to play with liquid nitrogen and petri dishes on special “family nights”? Didn’t other families set fruit-fly traps on their camping trips and spend hours sucking the little buggers into bottles filled with mashed bananas and yeast?

When I expressed an interest in geology at the ripe age of nine, my dad did what (I thought) was normal fatherly behavior: he took me to the geology department at Caltech and formally introduced me to faculty members. Oh, and he also brought home two college textbooks and plunked them on my bed.

When my geology phase ended – by about fifth grade – he wasn’t too disappointed. He waited to see what would capture my imagination next. He made our interests – from film to art to opera – his own. And he fueled our intellectual curiosity with nearly limitless access to the local college bookstore. My clothes were almost exclusively hand-me-downs, but if I wanted a book, I could get it. DaVinci would have envied our home library: dozens of art books, shelves of science texts and British literature, and nearly every possible translation of the bible.

My dad was, above all, decent. You could not doubt his desire to be a good dad, a good husband, and a good son. This decency extended beyond the family to neighbors, colleagues -- even the government. Once, after completing his taxes, he realized he had miscalculated. His payment had been seven cents short. He taped a dime to an index card and mailed it to the IRS with the message, “Keep the change.”

My dad’s love for his children was uncomplicated. He wanted us to be happy and healthy, and if he felt we were on that road, he didn’t need to know much more. Dad was not verbose. On the phone when he had a way of saying “Well, I know your mom is dying to talk to you” five minutes into the conversation -- but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t communicative. You had to know how to listen to him.

For example, as the youngest child, I spent years watching the way dad prepared to welcome his children home for holidays. The evening before, he made a special trip to the store and stocked the cart with sugary childhood favorites. These might have been confections we hadn’t really liked since we were twelve, but dad still believed that we wouldn’t feel at home without Twinkies or Ding Dongs. Dad loved food. Dad loved us. By extension, Rocky Road meant, “I love you and I’m glad you are home.”

And then there were the newspaper clippings. For years, he kept the scissors near him when he read the paper. If he saw something he thought his adult kids might enjoy, he’d clip it out and stick it in the mail – with nothing more than a yellow post-it that said, “Love, dad.” These clippings came in three general categories: Health, our professions, and comics. I have enough clippings on the link between red-hair and skin cancer to fill a scrapbook. We all got articles on rare genetic conditions that just might run in the family. For two years at college, I received a monthly stack of my favorite comic strips that didn’t run in the Boston papers. Edges neatly trimmed.

Dad, we hope you are up there having a decadent dinner with Darwin and Copernicus. We hope you get hours to explore the human genome. We hope you have two good knees, exceptional eyesight, and a perfect understanding of how much your family loves you.

Cheers,

Deborah

Deborah Farmer Kris, www.parenthood365.com